Shounak Das

Shounak Das

If you are here, I assume you are familiar with the terms “network programming” and “socket programming”. FYI, both these terms are used interchangeably as they are related concepts. Socket programming is a specific subset of network programming that focusses on communication between devices on different networks. It generally deals with the establishment, maintenance and termination of connections between applications. On the other hand, network programming is a much broader concept. It addresses the overall design and implementation of computer network infrastructures.

A quick google search on either term will give you results mostly in C/C++ and Python. The year is 2023, and people these days happen to prefer Python due to its simplicity and extensive modules. So, if you are familiar with Python, then I would recommend you to go through TCP and UDP client-server programs in Python. It will help you comprehend the wizardry of socket programming — the order of system calls might be confusing at the beginning.

When you compare the same Python code with its equivalent C/C++ program, you’ll notice that there is a lot more stuff happening in the later. This is because we have to define most of the things in C/C++. Whereas in Python, these are already pre-defined, we just need to put the values in proper places.

Before we begin, make sure you have a clear understanding of few essential concepts related to socket programming which, of course, I’m going to explain as simply and briefly as possible. Let’s see how a TCP client-server model is structured.

So let’s code this!

Like every other C++ program, we need to include the essential header files. We can also define macros for the port number and backlog (more on this later)

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define PORT 1337

#define BACKLOG 5

As we saw earlier, to set up a server/client, we need to create a socket which is basically an endpoint of communication over the network. Here’s the breakdown of the socket() system call.

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);

socket(). But over time, AF_INET has become more prevalent. Though it doesn’t make any difference, but using PF_INET is the more correct thing to do.0 to choose the appropriate protocol.int sockfd;

sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

Now we need to define the socket address structures. First, we need to understand the difference between sockaddr and sockaddr_in. Both represent socket addresses, but have different structures.

sockaddr: This is the generic structure used to define socket addresses. Most system calls accept arguments of this struct sockaddr.

struct sockaddr {

unsigned short sa_family; // Address family (e.g., AF_INET)

char sa_data[14]; // Address data

};

sockaddr_in: This structure is specific to IPv4 addresses and contains more details about a socket address. So, it is preferred to use struct sockaddr_in when defining socket addresses initially, and then typecast it to struct sockaddr when passing it as an argument to a system call.

struct sockaddr_in {

short sin_family; // Address family (AF_INET)

unsigned short sin_port; // Port number

struct in_addr sin_addr; // IP address

char sin_zero[8]; // Padding to make the structure the same size as sockaddr

};

in_addr is a structure used to define IPv4 addreses.

struct in_addr {

in_addr_t s_addr; // 32-bit IPv4 address

};

Looking at the structure of struct sockaddr_in (which we would be using for defining socket addresses for clarity and convenience), you can see that there are four members that need to be defined.

struct sockaddr_in server_addr;

server_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_addr.sin_port = PORT;

server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

We can skip sin_zero for now (no need for us to explore the deep waters so soon).

By now, you should be familiar with all the structs and constants that we used above, except INADDR_ANY. Well, it is special constant that binds the socket to all the available network interfaces on the host. This means, the socket will be able to receive incoming connections from or datagrams on any network interface.

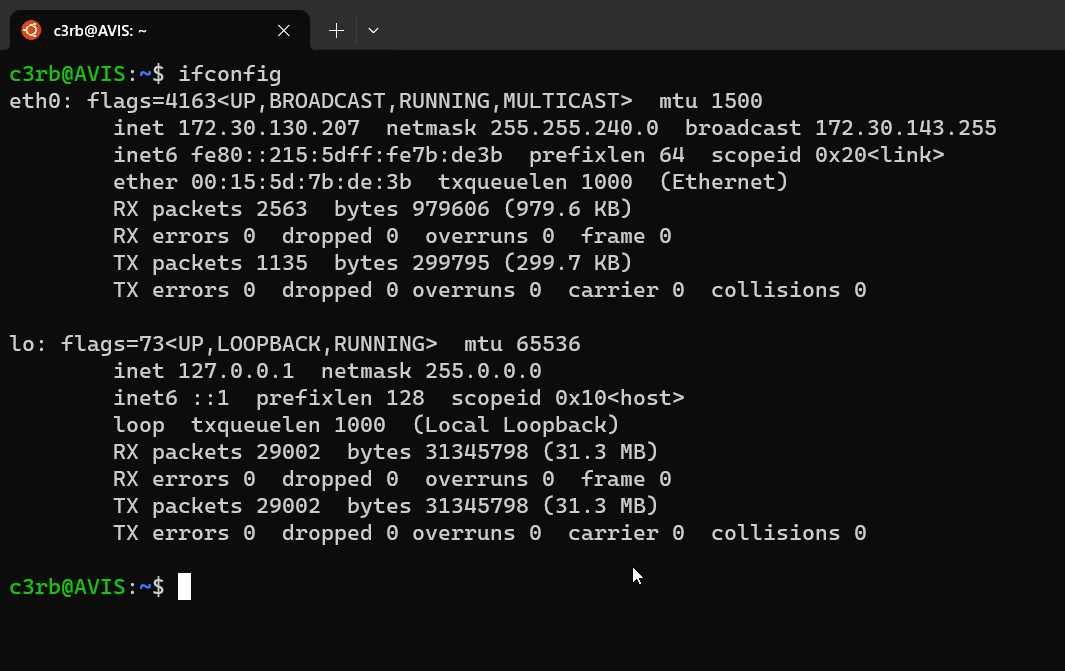

FYI, network interfaces are basically the physical or virtual points of connection between computer and network. Fire up a terminal or command prompt and run the command ifconfig (if you are on Linux) or ipconfig (on Windows). You should see something like this:

Here, eth0 is the ethernet network interface. There are other types of interfaces, for example, wlan0 for wireless interfaces and tun0 for VPN interfaces.

You can also specify a single interface to bind with the socket by using the inet_addr() function and passing a IP address string to it. This function will convert the string to struct in_addr.

sever_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr('127.0.0.1');

We are now set to finally bind the server address to the socket.

int bind(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *my_addr, int addrlen);

sockfd is the socket file descriptor, my_addr is a pointer to the socket address and addrlen is the length of the socket address. So, let’s bind the server address we defined in the previous to our socket.

bind(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&server_addr, sizeof server_addr);

If you are wondering what gibberish is written in front of server_addr, well, recall that in C or C++ we can typecast one data type into another by specifying the new data type in brackets just in front of the variable to be typecasted.

Now, our server is ready to start listening for incoming connection requests (or datagrams, for UDP sockets). We can do so by calling the listen() system call which looks like this:

int listen(int sockfd, int backlog);

You might have stumbled across the term “backlog” earlier in this article when we defined the macros. Backlog is an integer value that specifies the maximum number of connection requests on the incoming queue. Connections queue up until they are accepted by the server. If the connection request exceeds this number, they will be dropped resulting in HTTP error. The default value is generally around 20, but you can use a lower value here, say 5.

listen(sockfd, BACKLOG);

Now that our server is listening for connection requests, it needs to have the ability to accept a request. To do so, we use the accept() system call. It returns a socket file descriptor which contains information about the client, like IP address and port.

int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t *addrlen);

sockfd is the file descriptor of the listening socket, addr is a pointer to the local storage where client’s socket address information will be stored, and addrlen local integer variable that is set to the size of the client socket address (struct sockaddr *addr).

int clientfd;

struct sockaddr_in client_addr;

socklen_t client_len;

client_len = sizeof client_len;

clientfd = accept(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&client_addr, &client_len);

That’s it! Our server is ready to send() and recv() data from the client now. So many system calls and structs might be headache at the beginning. So let’s take a look at the sequence of system calls that we made:

socket(); // Initialize socket file descriptor

bind(); // Associate the socket with a local port

listen(); // Wait for connection requests from client(s)

accept(); // Complete the connection by accepting a client's request and initiating a client-server TCP communication channel

This was the server.cpp. Now, pause here and try to figure out what the client.cpp might look like. As you already know, we must create a socket in order to communicate with devices on other networks. But we don’t need to open a port to listen for incoming connections (that’s server stuff). What we should rather do is send a connection request to a server using the connect() system call. That’s all. We are then ready to communicate with the server.

int connect(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *serv_addr, int addrlen);

sockfd is the socket file descriptor, as always. serv_addr is a pointer to the server’s socket address and addrlen is an integer value specifying the size of this address.

int sockfd;

struct sockaddr_in server_addr;

server_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_addr.sin_port = PORT;

server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

// Initialize socket

sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// Connect to server

connect(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&server_addr, sizeof server_addr);

This is what your client code should look like till now. To send data, we use the send() system call. And to receive data, we use the recv() system call.

int send(int sockfd, const void *buff, int len, int flags);

int recv(int sockfd, void *buff, int len, int flags);

Here, buff is a pointer to the data being sent or received. len is the length of the data in bytes and flags control the behavior of the operation. We can set it to 0.

// server.cpp

char buff[1024];

while (1)

{

recv(clientfd, buff, sizeof buff, 0);

cout << "Message received: " << buff << endl;

}

// client.cpp

char buff[1024];

while (1)

{

cout << "\nEnter message: ";

fgets(buff, 1024, stdin);

send(sockfd, buff, sizeof buff + 1, 0);

cout << "Data sent successfully." << endl;

}

That’s it. After we’re done, we can close the socket using the close() system call.

close(sockfd);

Server:

//server.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cstring>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define PORT 1234

#define BACKLOG 5

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int sockfd, clientfd;

char buff[1024], ipstr[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN];

struct sockaddr_in server_addr, client_addr;

socklen_t client_len;

client_len = sizeof client_addr;

server_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_addr.sin_port = PORT;

// server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr("127.0.0.1");

server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

// Initialize socket

sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// Bind socket to local port

bind(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&server_addr, sizeof server_addr);

// Start listening on opened port

listen(sockfd, BACKLOG);

cout << "Listening on " << PORT << "..." << endl;

// Accept connection request from client

clientfd = accept(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&client_addr, &client_len);

inet_ntop(AF_INET, &client_addr.sin_addr, ipstr, sizeof ipstr);

cout << "Accepted connection from " << ipstr << ".\n"

<< endl;

// Recieve messages from server

while (1)

{

recv(clientfd, buff, sizeof buff, 0);

cout << "Message recieved: " << buff << "\n"

<< endl;

}

}

Client:

// client.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cstring>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define PORT 1234

using namespace std;

int main()

{

int sockfd;

char buff[1024];

struct sockaddr_in server_addr;

server_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_addr.sin_port = PORT;

server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

// Initialize socket

sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

// Connect to server

connect(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&server_addr, sizeof server_addr);

// Send message

while (1)

{

cout << "\nEnter message: ";

fgets(buff, 1024, stdin);

send(sockfd, buff, sizeof buff + 1, 0);

cout << "Data sent successfully."

<< endl;

}

}

I have created a GitHub repository where I have uploaded both these programs. I’ll be updating it with more network programs soon. Go fork this repo to your own GitHub. Thanks for reading.

84ck_783_914n37